Niles Union Cemetery

The story of the Niles Union Cemetery is unlike any other cemetery in Trumbull County, as it is a phoenix, having risen from the ashes following great destruction. Originally known as the “Jack Oak Burying Ground'' for the type of trees which populated the grounds during the early 19th century, this cemetery got its start in 1806 when Hannah Heaton, the six year old daughter of James Heaton––Niles’ founding father, passed away and was buried in what is now the southeast corner of the cemetery. Initially only an acre in size, the first burials were largely confined to an area around Hannah’s grave. Members of the Heaton family made up the first few decades of burials, so much so that it’s said that in 1835 an unnamed settler upon examining the cemetery stated “why this township is all settled by Heatons, and they are all dead!” However, by the late 1830s, as the community of Niles grew bigger and more people filled in, the cemetery started to expand outwards upon the full acre of land with burials gradually fanning north towards Niles-Cortland Road and an undeveloped tract of land to the east. On March 28th, 1863, upon being deeded to Weathersfield Township by Oliver and Henry Kyle, the Jack Oak Burying Ground became the Niles Union Cemetery, and with this transaction, gained an additional 1.08 acres of land. In 1870, wealthy ironmaster William Ward, who owned land directly east of the cemetery, sold Weathersfield Township trustees 8 acres of land, which when added onto the first two plots, totaled the cemetery's size to a square ten acres. Subsequently seeing more additions in 1873, 1895, 1905 and 1915; by time expansion ceased in 1930, the cemetery had grown to a rolling 40 acres in size, with the original “pioneer” tract surrounded by new lots and gradually falling into disuse. In the 1970s, as Niles (and much of the Mahoning Valley) was on the decline due to deindustrialization, the Niles Union Cemetery faced its own challenges: vandalism and a lack of upkeep. While both of these traits are by no means unique to this cemetery alone, they were nothing compared to the events that occurred a decade later on May 31st, 1985.

Springtime’s lush bloom is apparent in this scene overlooking the oldest section of the Niles Union Cemetery, formerly known in early days as the Jack Oaks Burying Ground. On the left is the grave of Hannah Heaton, the first burial in the cemetery.

On that day, Niles was struck by a phenomenon with such uncommon fury thatit has yet to be matched by anything like it in our area’s past, present, or likely future: an EF-5 tornado with winds upwards of 300 miles per hour. Spawning in Portage County near the Ravenna Arsenal, the cyclone tore through Newton Falls before entering Niles from the west. With Niles Union Cemetery directly in its path, the historic cemetery took a direct hit. First the stately trees that lined Niles-Vienna Road and then the oldest section where a multitude of fragile 19th century markers were damaged––including those belonging to members of the Heaton family. Tracking east, the vortex continued through the cemetery, decimating swaths of the newer additions where headstones of solid granite or marble sat, along with a sturdy brick mausoleum that had its roof ripped off. Whether pulled forward from their bases, pushed completely back, or placed upon the ground as if by unseen hands, within days of the storm, the extent of the damage had become apparent: over 800 headstones had been damaged by the tornado in some way, shape, or form. Almost immediately, restoration commenced, with the Niles Monument Co. spearheading efforts. Initially hired to fix only 200 headstones by paying family members, Monument Co. owner Jim DeChristefero would reflect in a 2020 interview that this number soon surged to about 500 simply due to the amount of markers that were either unclaimed by the living or hindered the restoration process as a whole. With headstones righted and reset, and the throng of debris cleared from the grounds that October, the next stage of recovery was replanting trees that had been lost in the storm, mainly along Niles-Vienna Road and the various driveways within. Currently an idyllic resting place for both Niles earliest pioneers and recently departed, the Niles Union Cemetery, or Jack Oaks Burying Ground as it was once called has rebounded to its original appearance with little hint as to what occurred on that terrible May day, and will remain a trove of local history for decades to come. In order to easily find the graves featured in this presentation, markers are listed in order of appearance as one walks through the cemetery, starting at the Niles-Vienna Road driveway with a focus on the oldest section of the cemetery. Photographs are also included for easy identfication.

Although the ‘85 tornado did substantial damage to the Niles Union Cemetery, many headstones were righted in due time and restored to their former splendor. Due to these efforts, many headstones remain intact today, like that of Jane Horner, who died in 1830.

James Heaton: Niles’ Founding Father

Perhaps one of the best known historical figures of this area, largely due to being mentioned in Bruce Springsteen’s 1996 hit song “Youngstown” which acknowledges his role in establishing the first blast furnace in the Mahoning Valley, there was something else James Heaton was: Niles’ founding father. The son of Isaac and Hannah (Bowen) Heaton who had twelve children total, James was born on February 2nd, 1772 at Berkeley, Charles City County, Virginia; a small settlement southeast of Richmond along the James River. Spending only 15 years of his life here, Heaton, along with the rest of his immediate family, would pack up their belongings in 1786 and relocate to Greene County, Pennsylvania where upon settlement, his father established two charcoal powered iron furnaces near Clarksville. Married in 1790 to Margaret Williams, with whom he had four children within the span of ten years, around 1802 James left his family behind in Greene County for a while and along with his brother Dan, came to Northeast Ohio, settling at present day Struthers. Armed with knowledge of ironmaking from their fathers’ ventures back in Greene County, the men saw Yellow Creek with its rich iron ore deposits and thick forests for charcoal as the perfect place for a furnace. Completed that year, the furnace was named “Hopewell” after an earlier industry of the same type back east in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Not only the first furnace in the Mahoning Valley, but in Ohio and west of the Alleghenies also, the brothers hoped that their operation would be as successful as its namesake back east, however this was not so. By 1806, the brother’s partnership dissolved, resulting in it being sold off, and by 1812, the furnace had been “blown out” as the War of 1812 called many of the ironworkers away from their jobs. However, by that point in time, James Heaton had long focused his efforts elsewhere: 15 miles up the Mahoning River at a place called Heaton’s Furnace, or as it’s called today, Niles.

Standing roughly seven feet tall in height, James Heaton’s headstone is a unique brownstone obelisk, carved around 1823 upon the death of his wife Margaret. His name would be added to the monument following his death in 1856.

In 1806, following the collapse of the Heaton brothers’ venture at the Hopewell Furnace, James relocated with his wife and family to Howland Township and then from there, to Wethersfield. Settling at a spot near the juncture of the Mahoning River and Mosquito Creek, he purchased a tract of land along the creek running a mile and a half north of the river. Constructing two mills along Mosquito Creek in 1807, these enterprises, a sawmill and gristmill respectively, would become the first industry of any kind in the community. Two years later in 1809, Heaton added to the unnamed community’s industrial might by constructing a blooming forge, a type of iron furnace that produces wrought iron from pig iron. Although this operation produced the first wrought iron made in the state of Ohio, Heaton was still unsatisfied, and in 1812, erected another furnace, located adjacent to the blooming forge along Mosquito Creek. Modeled after the Hopewell Furnace in Struthers, and improved upon, when completed the new furnace was christened “Maria” after James’ six-year-old daughter––the first non-native child born in Weathersfield Township and only child of his born in the Mahoning Valley to make it to adulthood. Around this time, the area in which James settled began to gain a name, “Heaton’s Furnace,” as more and more early pioneers realized it was not only a place where they could purchase ironwork, but settle at as well. By 1834, Heaton’s Furnace had grown into a village, and James, realizing so, handed over control of his furnaces to his sons and drew up an appropriate town plat, squared off lots, and marked streets. Along with these changes came the need for a new name. A man of intellect and principles, Heaton was a devoted reader of the Baltimore based, Whig leaning newspaper The Niles Register, published by Hezekiah Niles. With this, he named the new village “Nilestown,” however in 1843, it was shortened to “Niles” by the Post Office Department for convenience. With the arrival of the Pennsylvania–Ohio Canal in 1839, the community grew even more, and from then onward, became one of the main industrial cities of not only Trumbull County, but the Mahoning Valley as a whole until deindustrialization set in. On December 6th, 1856 at the age of 85, James Heaton passed away at his son Isaac's house in Salem, Marion County, Illinois. Returned back to Niles, he was interred at the Union Cemetery next to his wife, Margaret who died in 1823 beneath a unique brownstone obelisk, surrounded by various other members of the Heaton family.

The top portion of the marker features a distinctive sunburst motif along with a carver’s signature––that of Cornelius Ferris, a Cleveland area carver who is discussed in-depth in the Old Mahoning Cemetery guidebook. Also included are Margaret Heaton’s initials and the following verse: “No sculptured stone/Nor monumental brass/Can add to her/In whom those virtues shone.”

Naomi Eaton: Counting Differently

Upon first glance, the headstone of Naomi Eaton doesn’t appear to be much different from the headstones surrounding it. Other than being slightly taller and thicker than most, it is made of sandstone and is of the three-shouldered ‘headboard” type, popular during the early 19th century. Topped with a typical no-frills willow motif, it isn’t until one starts reading the epitaph that one gets a feel of what makes this marker so unique: it states Naomi Eaton was born on “Dec 2nd, U.S. 4” and died “on the 5th of Nov U.S. 43.” While nothing is amiss with the months, it is the years that catch passerby’s off guard, as instead of bearing expected numerals from the 18th and 19th century as other stones in the cemetery; this stone seems to date from the 1st century––long before the United States even existed! How is this even possible, and why does this headstone utilize such a format? The answer likely lies with Naomi’s eccentric husband, Daniel.

Regular in appearance, it is the epitaph on Naomi Eaton’s headstone which stands out: “Naomi Eaton wife of Dan Eaton was born Dec 2nd U.S. 4 & on the 5th of Nov. U.S. 43 became like unto a potters vessel that was stripped of its glazing and gliding, but as she believed the work would not be lost but would be molded in another form and become fit for the Masters use.” Given the unique dating format, which dates from when the United States declared independence from Great Britain, one has to wonder if Naomi’s eccentric husband, Dan who shunned religion and embraced politics was involved in the making of the headstone.

Born Naomi Hill in Frederick, Virginia as the third out of nine children to Robert Henry Hill and Priscilla Bowen, Naomi, or “Amy” as she was called, like the Heatons, relocated with her family from Virginia to Greene County, Pennsylvania in the closing decades of the 18th century. In 1795, while residing here, she became acquainted with a man named Daniel Heaton, whose father was an ironmaster out of Clarksville. Marrying him that year at only 15 years old, the couple lived together in Pennsylvania until just after the turn of the century. In 1802, with Naomi staying behind, Daniel left Greene County coming to Northeast Ohio along with his brother, James. Arriving at what is now Struthers, the men erected a blast furnace along the banks of Yellow Creek, a venture which was operated by the brothers for only three years until their partnership dissolved in 1806. Following his brother up the Mahoning River to the confluence of Mosquito Creek, although a bit later than he, shortly after it was settled, Daniel soon beckoned his wife and children to join him at the new community of Heaton’s Furnace. Arriving here with her six children, Jacob, Bowen, Isaac, Hannah, Ann, and Amy, Naomi lived a comfortable life here, as her husband was a respected member of the community. Not only the brother of the town’s founding father, he was also knowledgeable when it came to politics, so much so that in 1813, he was elected to represent Trumbull County in the State Senate. Nonetheless, Daniel was an odd fellow, personally at least. A “pronounced deist and a most outspoken unbeliever” who according to the 1882 History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties despite his beliefs encouraged religious debate within his home, entertaining itinerant ministers and even Samuel Smith, the brother of Joseph Smith––founder of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Around the time of becoming a state senator, Daniel went through the trouble of not only shortening his given name” to “Dan,” but his entire side of the families’ last name from “Heaton” to “Eaton” citing the presence of “superfluous letters.” Unfortunately, in 1818, Daniel, or Dan as he was known by this point in time, was left a widower when Naomi, his wife of 23 years passed away at the age of 37. While it is not precisely known if Daniel directly influenced the stonecutters hand while carving this unique marker, traits of his eccentrics are evident on the epitaph: Instead of bearing dates in the traditional anno domini format which counts the years from Christ’s birth, the marker counts years since the United States declared independence from Great Britain. “U.S, 4” corresponds to 1780, four years after 1776, while “43” corresponds to 1818––43 years thereafter. Nonthless, Naomi Eaton’s headstone is one of a kind not only in Trumbull County, but possibly the United States as a whole, with the 1882 History of Trumbull and Mahoning “doubting if another instance of the use of the year of the United States instead of Anno Domini can be found in all tombstone literature of the country.”

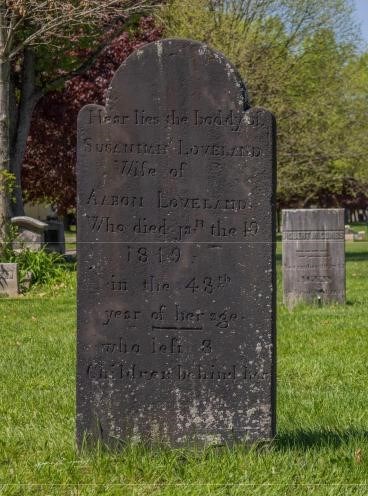

Susannah Loveland: Who Left 8 Children Behind Her

Up until relatively recently, at least in the realm of human history, to have a large family with many children was seen as the norm. As with high mortality rates and a tough workload needed to sustain a living, having multiple children ensured that at least some would make it to adulthood to carry on the family name. By the early 19th century although the Industrial Revolution was in its infancy when Trumbull County was settled, this trend was by no means extinct with many pioneer families having anywhere from five to seven children. For early Niles resident Susannah Loveland, she was one of the matriarchs of these large families having eight children in total. The fifth out of eight children born to John and Lydia (Taylor) Chapman of Glastonbury, Hartford County, Connecticut, born around 1771; one can’t help but to wonder if she was destined to have a large family from the start. Marrying Aaron Loveland, a fellow native of Glastonbury on October 1st, 1789 at the tender age of 18, just a year later on December 6th, 1790, she entered motherhood with the birth of her first child, Harriet.

Unpolished and even crude compared to the headstones around it, the mudstone marker of Susannah Loveland is marked by antiquated wording and rustic spelling with the phrasing “hear lies the boddy of.”

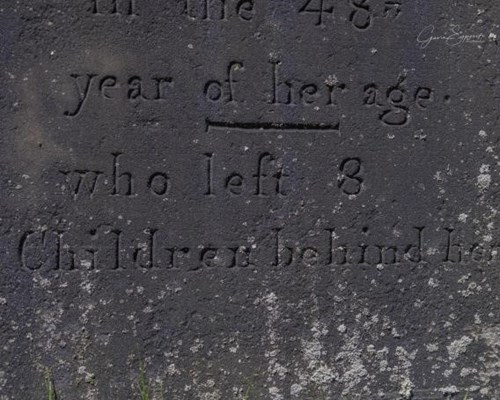

From thereon over an almost 20-year span from 1792 until 1811, seven more children would be born to the couple: Horace in 1792, David, in 1796, Lucy, in 1799, Lucinda, in 1802, Aurora, in 1805, Asel in 1807, and lastly Eliza in 1811. In 1812, perhaps at the prompting of her husband who saw the fertile lands of the Western Reserve as more suitable for raising a large family than that of Connecticut, Susannah would come to Trumbull County along with eight children in tow. Settling at Niles, her life here in Ohio was brief, lasting only seven years as on January 19th, 1818, she passed away at the age of 48 years. Interred at the Niles Union Cemetery in the original pioneer tract, then known as the ‘Old Jack Burying Ground,” her grave is topped by a typically shaped headstone of the era made of mudstone––a charcoal-colored sedimentary stone. However, compared to those around it, it is incredibly crude, as the lettering is plainly cut, the phrasing antiquated, and the spelling nonstandard. Heralded by the phrase “here lies the body of” ––spelled here as “hear lies the boddy of” –– by the time of Susannah’s death, this wording would have been out of date and almost Puritanical, replaced by the more remembrance-oriented wording of “in memory of.” Although plain and unrefined as it may be, the marker commemorates Susannah’s lot in life as a mother, noting on the epitaph that in death she “left 8 children behind her.” Her husband, Aaron who died in 1849 rests nearby, while all her children made it to adulthood, living relatively full lives.

For all works cited used to build this article please click here.

Susannah Loveland’s headstone makes note of her lot in life as a mother, with the epitaph stating that in death, she “left 8 children behind her.”

Basic Info

Website